The Eilshemius Phenomenon

Louis Eilshemius, Supplication (Rose Marie Calling), 1916; private collection.

Eilshemius’s submission to the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibition attracted the attention of Marcel Duchamp who declared it to be one of the best paintings in the show. The painting was the centerpiece of a 1933 exhibition at the Valentine Gallery.

————

Valentine Dudensing’s true love was the School of Paris and yet, during the two decades that the Valentine Gallery was in business, he sold more paintings and drawings by Louis Eilshemius (1864-1941) than any other artist. Dudensing may have first learned about the eccentric American artist when Marcel Duchamp singled out Supplication (Rose Marie Calling), the painting that Eilshemius submitted to the first Society of Independent Artists exhibition that opened in New York in April 1917. (This non-juried show was the same one that famously rejected Duchamp’s pseudonymously-signed urinal entitled Fountain.) Eilshemius confidently valued his painting at $15,000 making it the most expensive work in the show. Was Duchamp’s praise an ironic response to the high value, a glaring juxtaposition to the awkwardly painted nude? Even if his acclaim was in jest it was often repeated and served to bolster Eilshemius’s reputation for years to come.

Katherine Dreier, an organizer of the Independents show with Duchamp, gave Eilshemius his first solo exhibition at the Société Anonyme in 1920 followed by a second in 1924. At the time Valentine Dudensing was a salesman at the Dudensing Galleries, his father’s gallery, in New York. If he hadn’t noticed Eilshemius’s work in 1917, he noticed it now. He later wrote: “The New York art world was surprised and stirred [by Eilshemius’s paintings]; many new converts were made.” Dudensing was one of them and he subsequently arranged for an exhibition of Eilshemius’s paintings to open at the Valentine Gallery in the fall of 1926. He made a few sales to his top collectors but the reviews were harsh. While the paintings were described by at least one critic as “poetic,” so, too, were they called “lamentably amateurish.” Dudensing did not organize a follow-up show.

The Depression brought significant changes to the New York art market. During the late 1920s, increasing interest in the work of the School of Paris painters resulted in new galleries opening and existing galleries adding modern art to their programs. From his comfortable advantage in the field, Dudensing watched the competition grow and presciently noted in his letters to Pierre Matisse, his Paris-based partner, that the lesser quality works being imported were going to harm the market. Indeed, a backlash followed. Critics noted the increased number of mediocre paintings arriving from Paris and began calling for dealers to support American artists instead. This call grew louder with the onset of the Depression and by the fall of 1931 the term, “The American Wave,” began appearing in the press and referred to a resurgent interest in art that was fundamentally American. Writing for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Helen Appleton Read declared that “The Paris label has ceased to be a mark of artistic sophistication. To proclaim derivation from the Ecole Paris is to stamp one’s self as definitely prewar and out of touch with the main current of American art.”*

In late 1931 Valentine Dudensing saw an opportunity in the market shift toward American art. Louis Eilshemius, who was 67 years old and had stopped painting a decade earlier, was a prolific artist who had made few sales. He reportedly kept over 5,000 works in his Fifty-seventh street townhouse conveniently located down the street from the Valentine Gallery. Dudensing signed an exclusive contract with Eilshemius and, in a stroke of marketing genius, billed him “An Authentic American Artist.” Dudensing’s campaign began in February 1932 when he presented over three decades’ worth of paintings divided into two groupings that he labelled himself; the two-part exhibition opened with twenty-four examples from the "Period of Searching and Concentration, 1889-1910 'Romantic Drama'" followed in March with eighteen paintings from the “Period of Creation and Freedom, 1911-1920 'Lyrical Poetry.'" By April Dudensing sold two works to museums: the Cleveland Museum bought Samoa, 1907, and Lillian Henkel Haass bought Coast Scene, 1908, as a gift for the Detroit Institute of Arts (see images of these and other works below). With Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s 1926 purchase of The Flying Dutchman, 1908, on display in her recently-opened museum and Duncan Phillips’s 1927 purchase of a Samoa painting for his public collection, Dudensing could now list the museums that owned Eilshemius’s paintings, affirmation of the artist’s reputation for prospective buyers that were considering the artist’s work. The dealer also announced his ambitious plans for Eilshemius exhibitions in Paris, Berlin, and London to take place during the summer of 1932. Ultimately only the Paris show materialized though it was impressive and considered a major success: forty-five paintings were shown at the prestigious Galerie Durand-Ruel for two weeks in June. Henri Matisse reportedly visited the exhibition and became an admirer and, in a major coup, the Louvre purchased the 1918 painting, The Gossips. As a result, Dudensing could also claim the French seal of approval: “I know many serious Parisians who agree with me that Eilshemius is always a poet who had dreams and who painted them with a lyrical charm.”

At a time of economic misery, Eilshemius’s pastoral landscapes and charming figurative vignettes offered an escape unlike the gritty paintings of the Social Realists. The artist’s stylistic range appealed to a broad clientele and with access to his extensive inventory, Dudensing could reach all level of collectors. An exhibition of watercolors he organized in May 1934 attracted many first-time art buyers who seized the opportunity to take home a piece by an artist who was represented in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection. The watercolors were priced at $50 and $75 and, with the endorsement of the New York Times critic who called them “serious works of art,” the show was “literally strewn with the red stars of purchase.”**

Though Louis Eilshemius’s name has been lost to history, Valentine Dudensing was responsible for elevating the artist’s reputation to the forefront of the American art market. Between 1932 and 1945 the prestigious Valentine Gallery presented eleven solo exhibitions of his paintings and, in addition to the Metropolitan, Whitney, Phillips, and Cleveland, he also sold works to the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford; Boston Museum of Fine Arts; Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts; and the Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts. Leading collectors of modern art bought Eilshemius’s paintings as well, including Stephen C. Clark, George Gershwin, Chester Dale, Walter P. Chrysler Jr., Adelaide Milton de Groot, Robert H. Tannahill, and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. Victor Ganz, who went on to form one of the most important Picasso collections in the country, made his first art purchase—a watercolor by Eilshemius—in 1934 when he was 21-years-old. Joseph Hirshhorn and Roy Neuberger were among the most avid collectors; the latter gave a number of Eilshemius works to museums across the country.

————

*“In the Galleries: Wide Variety of Group Shows Offered by Dealers –French Art at Kraushaar’s—American Scenes and Subjects at Rehns’s” (October 4, 1931), p. E5.

**Edward Alden Jewell, “Louis Eilshemius” (May 4, 1934), p. L19.

The Flying Dutchman, 1908, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Gift of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney.

Samoa, 1907, Cleveland Museum of Art

Samoa, 1907, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

The Gossips, 1918, Louvre Museum, Paris. Now housed at Blérancourt, French-American Museum of Blérancourt Castle, France

The Rejected Suitor, 1915, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Delaware Water Gap, c. 1895-1900, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1932

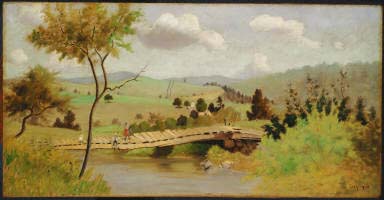

Adirondacks: Bridge for Fishing, 1897, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Springtime, c. 1901, watercolor, Worcester Art Museum