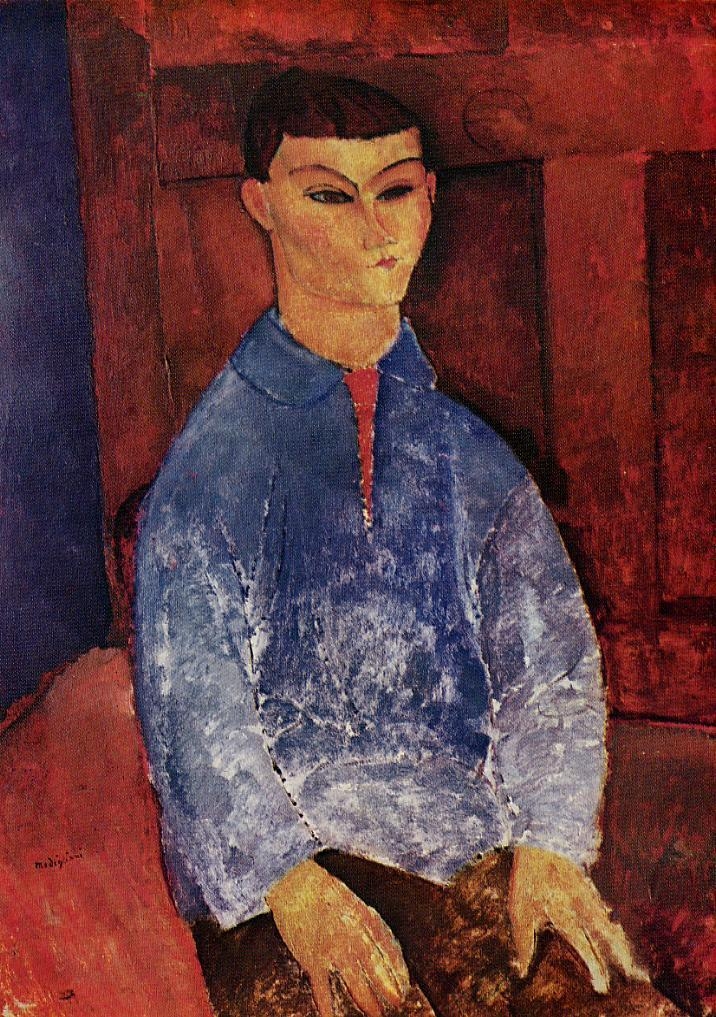

"I have never seen a better group of Modiglianis than that now installed at the Valentine," wrote Edward Alden Jewell for the New York Times.* He was referring to a selection of portraits on view at the Valentine Gallery in early January 1940.** All but one of the dozen paintings were from the collection of Paul Guillaume, the art dealer who met and began representing Modigliani in Paris in 1914. For the next two years the dealer guided the artist's career and, as Guillaume noted, he was the only one buying Modiglianis in 1915.

Paul Guillaume had been an important source of artwork for the Valentine Gallery since the late 1920s and, because of his business relationship with Valentine Dudensing, many of the best works from Guillaume's inventory are now in American museum collections. After Paul died in October 1934, his 36-year old widow, Juliette "Domenica" Guillaume, took over her husband's business. In 1935 Domenica began shipping paintings to New York to be exhibited at the Valentine Gallery with the hope that Dudensing would sell them to his American clientele. Many of the works that didn't sell were returned to Paris after the war and are now part of the Guillaume Collection at the Musée de l'Orangerie.

Dudensing published a checklist for the Modigliani exhibition but, because it lists only titles, the works are difficult to identify. From the gallery's sales records we know that Dudensing sold three Guillaume Modiglianis after the exhibition closed: Lola de Valence, 1915, to Adelaide M. de Groot (1876-1967), an artist and collector, in January 1941; the following month Billy Rose (1899-1966), the American entertainer, bought Jean Cocteau, 1916. In May 1943 Dudensing sold Jean de Rouveyre [actually a portrait of André Rouveyre], 1915, to Maria Martins (1894-1973), the sculptress and wife of the Brazilian Ambassador to the U.S. Only one painting in the exhibition was a loan: Lunia Czechowska, 1919, came from the collection of the Chester Dale Foundation. The painting was not part of Dale's bequest to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

Below is the checklist with my attempt to reconstruct the exhibition based on provenance information gleaned from catalogues and museum records; images of the works appear at the bottom of this page. Because I cannot confirm the inclusion of all the works with absolute certainty, I welcome input from readers who may have additional provenance information. Other paintings by Modigliani that passed through the Valentine Gallery and are in American museum collections today can be found in the section of this website titled "Artwork."

-----------

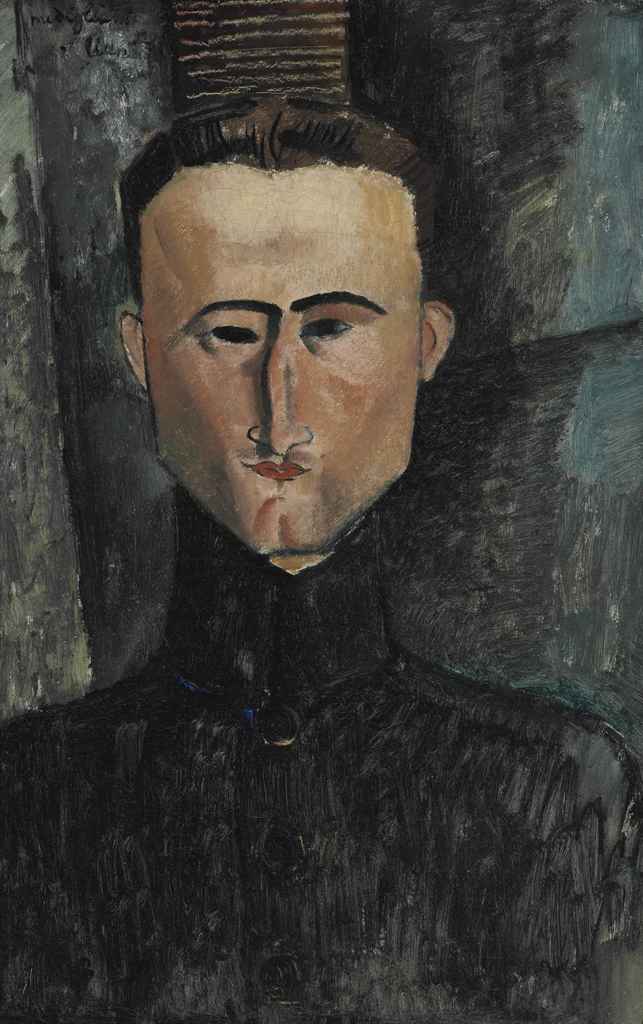

1) Jean Cocteau (1916, Princeton Art Museum, New Jersey; on long-term loan from the Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation)

2) Moise Kisling (c. 1915, Private Collection)

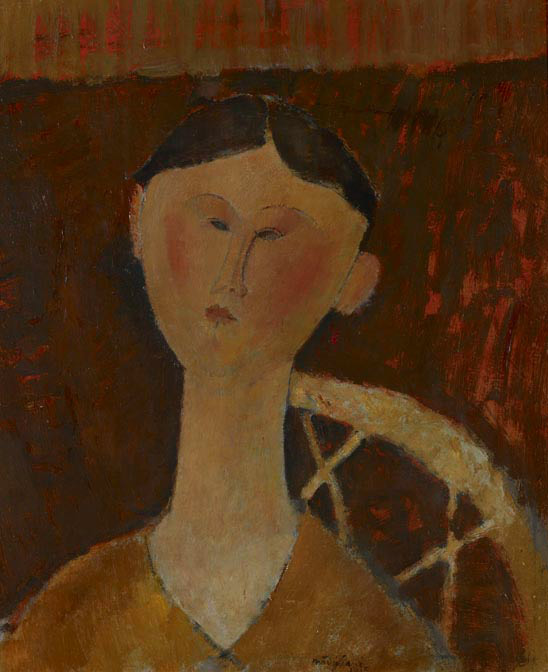

3) Mademoiselle R. (possibly misidentified portrait: Raimondo, 1915, Private Collection)

4) Lola de Valence (1915, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

5) Beatrice Hastings (likely 1915, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto)

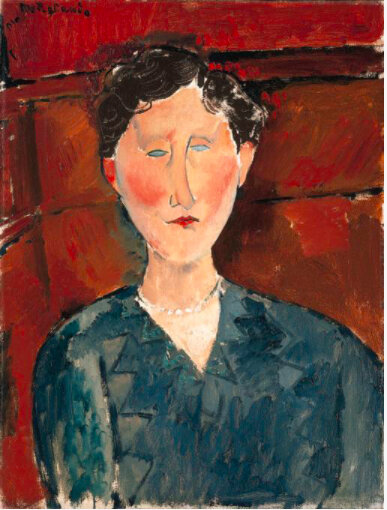

6) Antonia (c. 1915, Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris)

7) J. de Rouveyre (Jean de Rouveyre, 1915, Private Collection)

8) Madame C. (possibly Woman in Blue Dress [Mme. Cheron], c. 1916, Private U.S. Foundation)

9) Tête de Femme (likely Red-Haired Girl, 1915, Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris)

10) Portrait (possibly Woman with Blouse, c. 1917, Private Collection)

11) Femme au chignon (likely Woman with Velvet Ribbon, c. 1915, Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris)

12) Lunia Czechowska, loaned by Chester Dale Foundation (c. 1918, Private Collection)

*"Modern French Painting," The New York Times (Jan. 21, 1940), X9.

**The show ran from January 8 - February 3, 1940.

![3) Mademoiselle R. (sic) [Raimondo]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57d5b817ebbd1a582b533034/1625767810561-EWJFFROOQVOPZHBYCW4K/Screen%2BShot%2B2021-07-08%2Bat%2B2.08.36%2BPM.jpg)

![[Bird's eye view looking south from Fifth Avenue at 58th Street at the 26-story Heckscher Building (c. October 1921), southwest corner of Fifth Avenue at 57th Street, with Vanderbilt Mansion (since replaced by Bergdorf Goodman) in foreground]. 1921.…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57d5b817ebbd1a582b533034/1483369873376-HQJ0LJ0B9HLHQ1RM80WP/Heckscher+Building+jpeg.jpg)